by Dana Miller

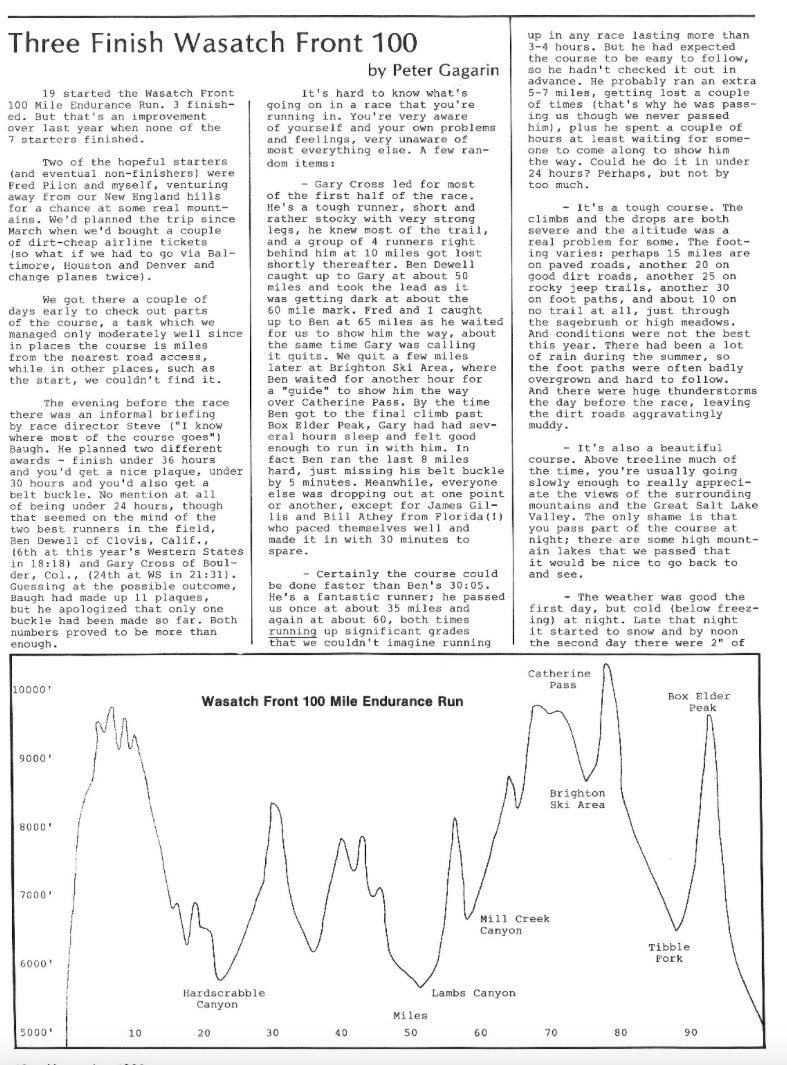

The 1982 Wasatch 100 was historic in more ways than one. First of all, after going 0 for 7 in 1981, there were actually 3 finishers. Secondly, the runners were treated to a snowstorm Saturday night. Finally, the very challenging course proved incredibly tough but do-able.

As you’ll remember, the 1981 Wasatch pretty well beat the crap out of the seven runners who started. Despite a talented and determined field, none of the seven starters made it past Lambs Canyon (mile 51). In reflection, Steve Baugh observed that the “no finishers notoriety” may have actually helped the race gain more interest from the small ultrarunning community. After all, what ultrarunner in her/his right mind wouldn’t be attracted to the challenge of being among the first finishers? Sounds like a modern-day Barkley, right?

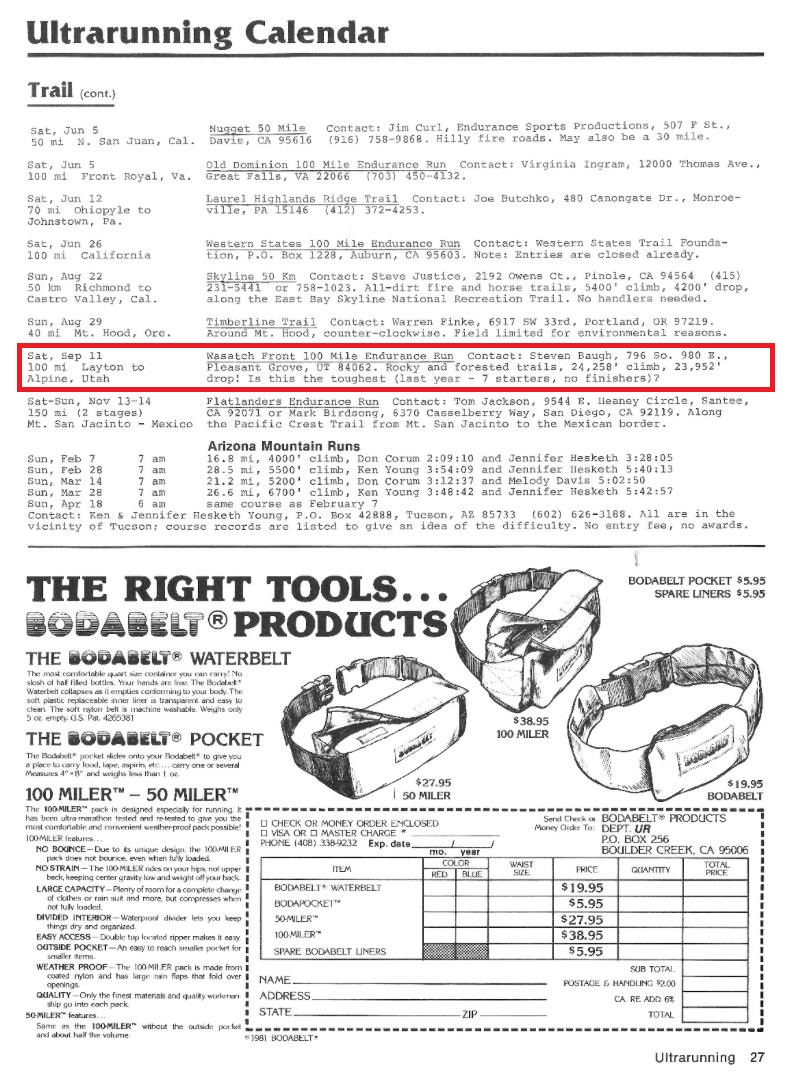

Partly due to its appearance in the fledgling (it was their first year of publication) Ultrarunning magazine’s race calendar, 19 runners toed the starting line, a 250% increase over the prior year. To put this in perspective, Western States started the lottery system in 1981 and had 278 starters in 1982. Old Dominion, in its third year, had 38 starters.

Announcement of the 1982 Wasatch 100 on the January-February 1982

Ultrarunning magazine race calendar (courtesy of Ultrarunning magazine)

The “race committee” also more than doubled in size. Steve Baugh and Evelyn Baugh (his patient and indulgent wife) were joined by Nancy Barraclaugh (pronounced “bear claw”) and John Grobben in supporting roles. Steve Baugh worked for the Leavitt Insurance Group as an insurance underwriter, and Nancy and John were insurance agents. Somehow, Steve convinced Nancy and John to give up a September weekend to help with the race. Nancy took charge of the aid stations. John worked the Affleck Park aid station. Little did Nancy and John know what they were getting into or how their lives would be impacted by “the Wasatch bug.”

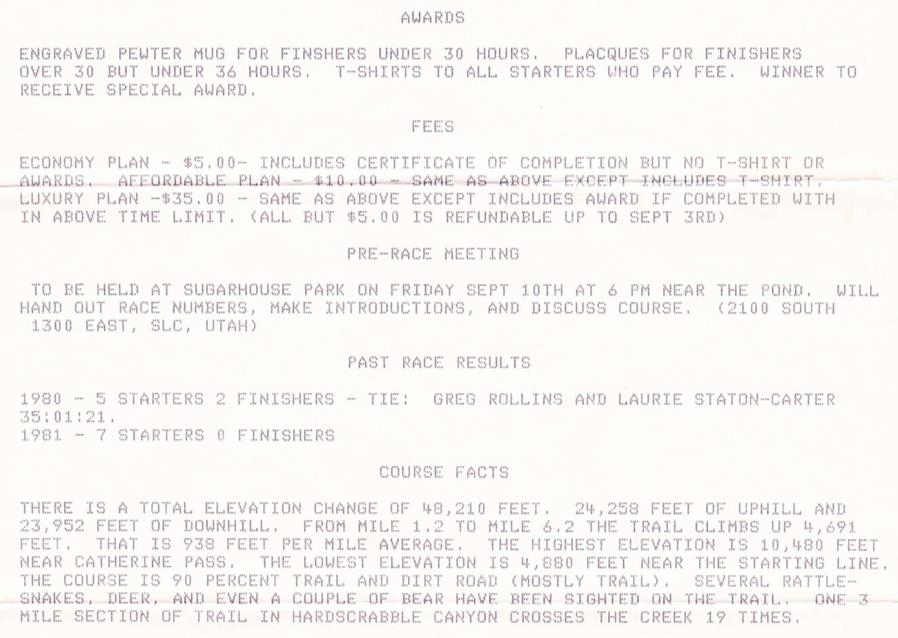

Steve Baugh’s race information letter (printed on a dot-matrix printer) listed potential awards as: An engraved pewter mug for all finishers under 30 hours and plaques for those finishing between 30-36 hours. However, runners had to pay extra if they wanted an award, even after earning it. The race entry fee even provided three options: Economy plan – $5.00 – included a certificate of completion but no t-shirt or award; Affordable plan – $10.00 – added a race t-shirt; and Luxury plan – $35.00 – certificate, t-shirt and finisher’s award.

Under the section entitled “Course Facts”, Steve provided the following information:

There is a total elevation change of 48,210 feet. 24,258 feet of uphill and 23,952 feet of downhill. From mile 1.2 to 6.2 the trail climbs up 4,691 feet. [Editor’s note: With the course change, it should have read “From the start to mile 5.0…”.] That is 938 feet per mile average. The highest elevation is 10,480 feet near Catherine Pass. The lowest elevation is 4,880 feet near the starting line. The course is 90 percent trail and dirt road (mostly trail). Several rattlesnakes, deer, and even a couple of bear have been sighted on the trail. One 3-mile section of trail in Hardscrabble Canyon crosses the creek 19 times.

Excerpt from the 1982 Wasatch pre-race letter

(courtesy of Rick May)

1982 Wasatch 100 Pre-Race Letter (click link for pdf)

Under the section “Suggested Items to Bring”, it should have been obvious to would-be entrants that they were in for an adventure. Steve recommended:

Water carrier [Editor’s note: Water bottle packs and bladder packs hadn’t been invented yet.], matches, flashlight, suntan lotion, snakebite & first aid kit, food, extra clothing, maps, and compass.

Steve’s entertaining and detailed narrative course directions were identical to the wheeled course set out for the 1981 race. In an August 12, 1982 letter to the entrants, Steve noted a slight change in the course:

There has been a slight change to this year’s Wasatch Front Endurance Run Course due to overgrowth of trail in one small section.

We will be eliminating the 1.2 miles of running on the paved road at the start of the course and adding this amount near the 51.1-mile point.

On page two of your directions scratch the following:

At 51.1 miles you must leave the main trail again. Another stream comes from the east and joins the creek you have been following… At this point you’ll probably be able to see Lambs Canyon Checkpoint. When the road turns paved you’ve gone 52.8 miles you are near the mouth of Lambs Canyon.

Now add the following:

Continue straight on the foot-path which gets better the further you go for about 1 ½ miles. You will come to a paved T-road, which is Route 65, the East Canyon road you were previously on. Turn left and follow this paved road for about 100 yards past an equipment shed on your left and turn left again on the first paved road. You need to turn before the freeway. There is a sign on that road that reads “George Washington Park Golf Course.” Follow this road uphill past the golf course for about 1 ½ miles and it will turn to dirt and gravel. Stay on it. Don’t go down to Washington Park. After about ½ mile the dirt road ends. You are parallel to the freeway, which is on your right. Climb up the side hill about 25 feet and walk along the side of the freeway on the outside of the rail for about 300 yards until you get to the Lambs Canyon checkpoint at 52.8 miles. Don’t cross the freeway. There is an underpass by Lambs Canyon checkpoint, which you can go under.

He added this encouraging comment:

This change will make the course easier to follow, eliminating a small section of bushwhacking.

The change did make the course easier to follow, eliminating several potentially confusing turns, stream crossings and a bit of bushwhacking. The 4-5 runners who got lost in the dark in this section in 1981 probably wish they could have taken the new, 1982 route. Perhaps they could have made it to Lambs Canyon and beyond. Who knows? That’s ultrarunning.

1982 Narrative Directions (click link for pdf)

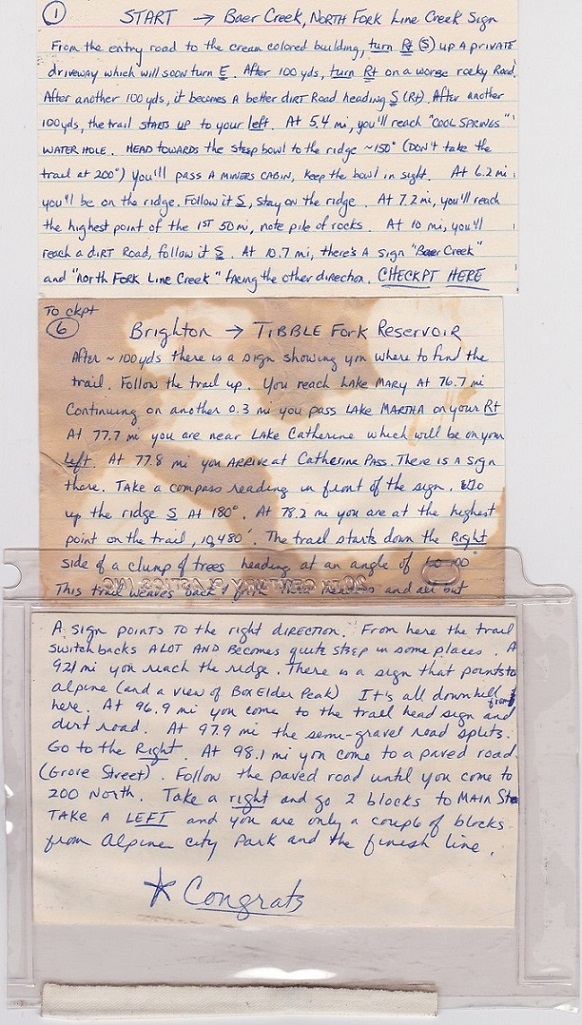

Steve also hung a few more ribbons. However, word was out that entrants really needed to do their homework, carry and closely follow the narrative course directions, carry a compass, and pay careful attention while on the course.

The starting field was very diverse, ranging from 4-time Western States 100 finishers to first-timers who seem to have entered Wasatch on a lark and at the last minute. Seven of the 19 starters had finished the Western States 100. Gary Cross (4 finishes), Ben Dewell (3), Bob Haynes (3) and David Ferguson (2) had completed Western States more than once. Peter Gagarin (co-editor of the fledging Ultrarunning magazine) had extensive competitive orienteering experience. We also can’t ignore race director Steve Baugh, making his third start (score: Wasatch 2, Steve 0).

On the other end of the spectrum were the brave, perhaps naïve souls who entered Wasatch with no ultramarathon or trail running experience and no firsthand knowledge of what they were getting into. Representative of this group was Alan Weeks, who entered the race on a whim but was enthralled by the promise of adventure. Alan writes:

Fall of 1982, I read an article at the bottom of the front page of the Salt Lake Tribune written by a UPI journalist. He spoke of a race, a trail run, ultramarathon, beginning opposite the Hill Field Road in East Layton, and ending at the city park in Alpine…a 100-mile distance!

He said the race crossed multiple mountain ranges and was the equivalent of running from sea level to the top of Mt. McKinley (now called Denali) at 20,310 feet – the highest point in North America – and back again! I smiled…I was hooked.

Having discovered a natural knack for distance running in the Marine Corps from 1969-71, I was a veteran of the Deseret News Marathon, St. George Marathon, and a multitude of 5k and 10k foot races. I’d hiked the Wasatch Mountains since I was a kid growing up at the base of Mt. Timpanogos in Pleasant Grove and later, as a teenager, near the base of Mt. Olympus and Lone Peak in Holladay. However, I’d never participated in a trail run.

I thought I’d treat myself to a new pair of running shoes. My wife and I visited Wolfe’s Sporting Goods in downtown Salt Lake City, and out of the $5 bin, I bought a pair of blue Asics/Tiger racing flats! (Did I mention I’d never done a trail run before?!)

Ben Dewell was at the other end of the spectrum from Alan Weeks. A Western States 100 finisher with a top ten, 18 hours 18 minutes finish just 10 weeks prior to Wasatch, he knew exactly what he was getting into. An accomplished cross-country skier, trail running was excellent cross training and a natural extension of his first-love sport. Ben trained hard all spring and early summer with hopes of running the 200+ mile John Muir trail in under 48 hours. Ben is quoted as saying: “I had gotten sick the day I was supposed to leave [for the Muir run] so, since I had all that Sierra trail training, I just re-designated all my equipment for the Wasatch run” (Fresno Bee, Sept. 23, 1982, pp D5-6).

Looking back to those early days of 100-mile running, it’s evident that the Western States 100 inspired challenge of “100 miles in one day” was huge. That motto is still engraved on the Western States 100 “under 24 hours” belt buckles.

Coveted Western States 100 sub 24-hour silver belt buckle “100 Miles – One Day”

(photo courtesy of Dana Miller)

Ben Dewell had finished Western States in under 24 hours in each of his first three attempts. The standard of covering 100 miles in less than one day was so ingrained in his “California ultrarunner” mind that even 35 years later, he recalls: “The whole idea of these races was to complete them within 24 hours. The only measure of success was to finish in under 24 hours.” This time standard begs the question, “What constitutes a legitimate 100-mile trail race finish”, but is far beyond the scope of this article.

The starting field included (listed alphabetically with Western States 100 finishes):

Joseph Adams

Bill Athey

Steve Baugh (Wasatch 100 start #3)

Gary Cross (WS 1979 – 23:17; 1980 – 23:31; 1981 – 23:18; 1982 – 21:31)

Ben Dewell (WS 1979 – 23:13; 1980 – 20:22; 1982 – 18:18)

David Ferguson (WS 1980 – 23:14; 1981- 23:06)

Peter Gagarin

James Gills (WS 1982 – 23:33)

Bob Haynes (WS 1980 – 26:52; 1981 – 23:42; 1982 – 26:38)

Howard Henry

Edward Hooper (WS 1981 – 29:21)

Leland Jonas

Dave Niederhaus (WS 1981 – 22:23)

Mel Olkowski

Fred Pilon

Bill Smith

Ross Thomas

Terry Thomas

Alan Weeks

The pre-race meeting was held at Salt Lake City’s Sugarhouse Park on Friday, September 10th, establishing a meeting location tradition followed ever since. A photo of the pre-race shows Steve Baugh giving instructions and Nancy Barraclaugh at the left of the picture. On the table in front of Steve is the pewter sub 30-hour finisher’s mug (it looks like it has an old-fashioned pistol as a handle); a sample plaque (30 to 36-hour finishers), copies of Ultrarunning magazine (compliments of co-editors Peter Gagarin and Fred Pilon); and the all-important quadrangle maps.

1982 Wasatch 100 pre-race meeting at Sugarhouse Park Race Director Steve Baugh giving instructions while

new race committee member Nancy Barraclaugh (with sunglasses left of Steve) looks on.

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

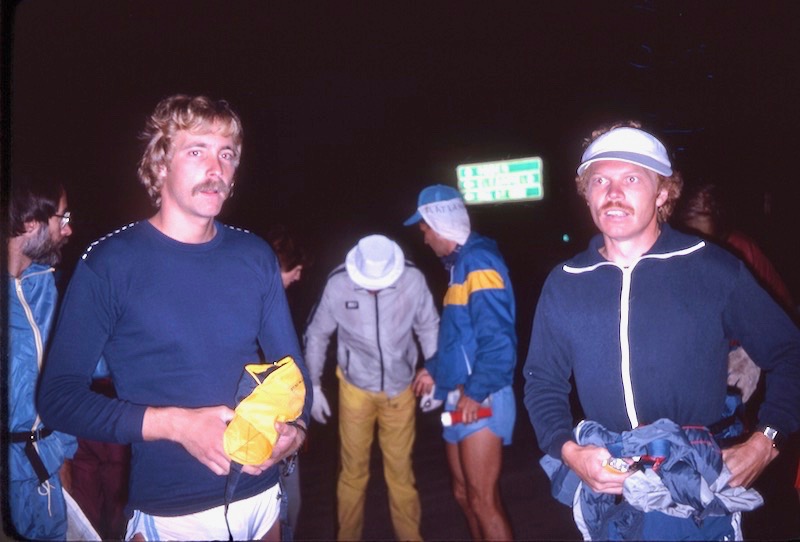

It rained most of the night between the pre-race meeting and the scheduled Saturday 5 a.m. start. Eventual winner Ben Dewell remembers that the rain stopped about a half hour before the start. When asked what was going on in his head before the race, he recalled thinking “Surely they can’t run the race in weather like this.”

Interview with eventual winner, Ben Dewell, about the weather on race day.

Audio Player

Ben Dewell (left) and Race Director Steve Baugh (right) at the start of the

1982 Wasatch 100 near Hill Field Road in East Layton, UT

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Alan Weeks, who would drop out between Lambs Canyon (mile 52) and Big Water (mile 60), recalls Wasatch’s early miles:

Saturday morning, 5 am…we were off! Climbing the trail in total darkness save the occasional flashlight beam, we trudged seeming straight up the mountain, arriving at the summit of Thurston Peak (9706’) after sunrise. I remember looking south…literally as far as one could see…to Lone Peak, some 40 miles away “as the crow flies”…at 11,260 feet. I remember thinking “no way” can a human being run “cross country” from here to there…even further…at all…let alone by the next afternoon. Inconceivable when you factored in running up and down several mountains!

Then we took off running! It had rained the night before and, as I recall, was raining lightly as we traversed the ridge south from Thurston Peak…headed for the Francis Peak radar tower, a huge white ball, way far off the distance.

Crossing Francis Peak’s face, I encountered the editors of Ultrarunning magazine, Peter Gagarin and Fred Pilon, from Massachusetts. They were crouched over a USGS quadrangle map, and with compass in hand, plotting their course! Between reading Steve Baugh’s printed course directions (which were amazing in their detail) and consulting map and compass…the three of us continued on in light rain to the radar tower.

Past the tower, the trail dropped steeply down the east side of Francis Peak. We were slip sliding in mud…balancing to stay on our feet…as we raced downhill.

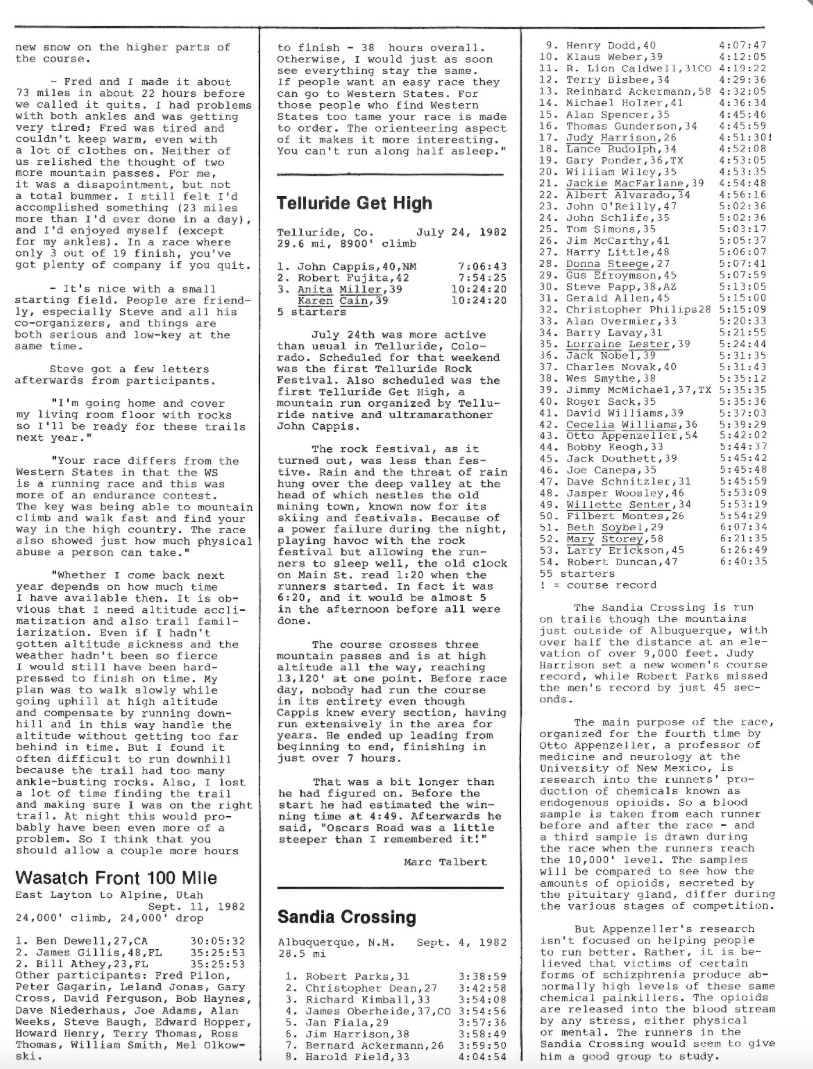

Describing the race’s early miles, Ultrarunning magazine co-editor Peter Gagarin wrote:

Gary Cross (Colorado) led for most of the first half of the race. He’s a tough runner, short and rather stocky with very strong legs, he knew most of the trail, and a group of 4 runners right behind him at 10 miles got lost shortly thereafter (Ultrarunning magazine, November 1982, pp. 12-13).

As the race unfolded, eventual winner Ben Dewell remembers “…being totally unconcerned with anyone else on the course.” With the challenges presented by the weather, a difficult course, poor (by today’s standards) course markings, and complex narrative directions, Ben found himself adopting the race mantra: “What else could happen?”

Eventual winner Ben Dewell just south of Francis Peak – 1982 Wasatch 100

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Well, getting off course could happen. From today’s modern trail ultrarunning vantage point and expectations, it’s difficult to fathom a virtually unmarked course (Ben Dewell “only remembers 3-4 spots in the first 50 miles that had any type of marking”) or relying on multi-page narrative directions and a compass to stay on course. That was, however, the reality of the 1982 Wasatch 100.

Handwritten narrative course directions (three of six 3X5 cards)

carried by Ben Dewell during the 1982 Wasatch 100.

(courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Ben Dewell was a member of that group of front runners who got off course in the early miles. From his description, it appears that the navigational error occurred at “The Narrows”, mile 22. The Narrows is, as the name implies, the end/entrance of a canyon. Runners had just survived 7 miles of trail-less route finding and obscure trail since leaving the still existing “maintenance sheds” 4-5 miles south and downhill from Francis Peak.

Ben Dewell leaves the “maintenance sheds” (mile 15.2) heading downhill towards the Narrows

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Based on the author’s course knowledge, it’s likely that the front runners turned left at the Narrows (mile 22) rather than right. That left turn put them on what appeared to be a well-established dirt road leading towards the small mountain town of Morgan. Unfortunately, they should have turned right, which would have taken them into the mouth of rugged Hardscrabble Canyon, its route-finding and nearly two dozen stream crossings. Eventually, the group realized their error, back-tracked up the muddy dirt road and got back on course. Gary Cross, with four Western States sub-24 hour finishes under his belt, was the early leader but Ben passed him before Lambs Canyon (mile 52). Gary dropped out at Millcreek Canyon (mile 65) just before midnight.

The damp conditions and on-and-off rain soaked the course, turning the clay-based trails into a gooey mess. Race committee newcomer and Affleck Park (mile 35) aid station boss John Grobben remembers runner arriving at his aid station with “mud-packed shoes and crushed egos.”

Interview with John Grobben, who set up an aid station at Affleck Park (mile 35).

Audio Player

Ben Dewell asks “This way?” at Big Mountain 1982 Wasatch. Note the empty parking lot.

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Ben discovered that running a fast time at Wasatch included challenges far beyond just running 100 miles. Route finding on the sparsely marked course, especially for an out-of-state, first timer, was challenging and a mental drain. In his recap of the race, Ultrarunning’s Peter Gagarin reported: “Fred [Pilon] and I caught up to Ben at 65 miles [Editor’s note: Upper Big Water on the current course] as he waited for us to show him the way, about the same time Gary [Cross] was calling it quits” (Ultrarunning, November 1982, pp. 12-13.) Ben’s “what else could happen” mantra of the day carried him into the night and the race’s final 35 miles.

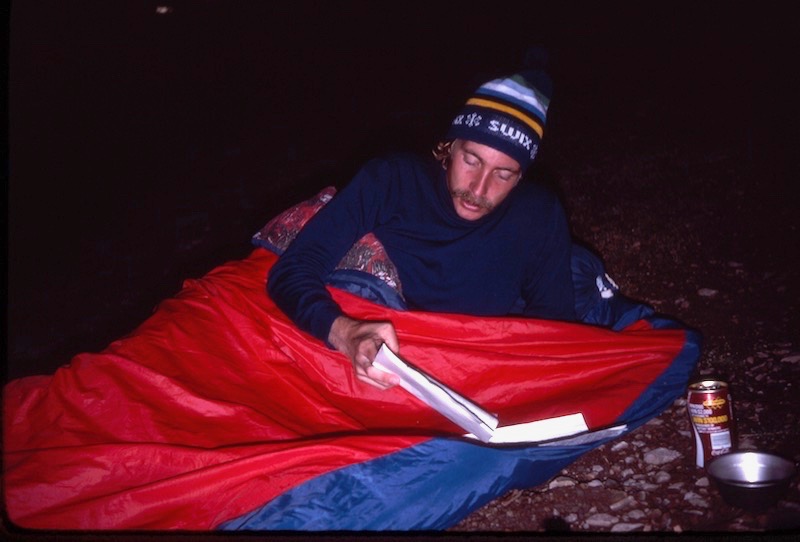

Arriving at Brighton ski resort (mile 75), Ben grappled with his “sub-24 hours is the only measure of success” expectations, thinking “What’s the point?” The struggle went from bad to worse when Ben’s wife, Mary, told him that “he had to wait for a guide” before continuing into the night and the final 25 miles. Huddled in a bivvy bag for warmth, Ben did just that…waited.

Race leader Ben Dewell waits in a bivvy bag for a “guide” at

Brighton (mile 75) 1982 Wasatch 100.

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

More than a half-hour later, high schooler Hans Despain arrived, assuming “guide” duties. Ben recalls that it was a mental relief to be free from being solely responsible for staying on course. Almost humorously, that all unraveled 3 miles later as the duo reached windy Catherine Pass, the course’s high point at 10,480 feet. There, just before dawn Sunday morning, guide Despain announced that he didn’t know where the course went. “Wait here,” he told Ben and promptly disappeared for 20-30 minutes to figure things out, pray, ask for help or whatever it took to identify the correct route. One can only imagine what went through Ben’s mind at that point, 24 hours into the race.

Eventual winner Ben Dewell describes arriving at the Brighton Store aid station (mile 75) where he was told he needed to wait for a “guide” before continuing towards the finish line.

Audio Player

Eventually, Hans returned with the less-than-reassuring comment: “I think I know the way”. Together, chased by an early season snowstorm, they navigated the intersecting game trails leading down into American Fork Canyon. The well-established trail leading west and up into the Lone Peak wilderness area was, by comparison, a welcome relief as they made their way towards the finish at Alpine.

Snow changed to rain as Ben and guide Despain descended into Utah Valley. Trail transitioned to gravel road and they were met by occasional weekend horse riders, fascinated by the runners’ scant attire and what they were doing in the mountains in such poor weather. Finally hitting pavement entering Alpine, Ben increased his pace, perhaps reminiscing about the infamous Auburn high school track finish at the Western States 100.

Ben Dewell and “guide” Hans Despain (white jacket) finally hit the gravel road above

Alpine after traversing the Lone Peak wilderness.

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Ben Dewell and guide Hans Despain nearing the finish line at Alpine.

Note the skiff of snow and low cloud cover.

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

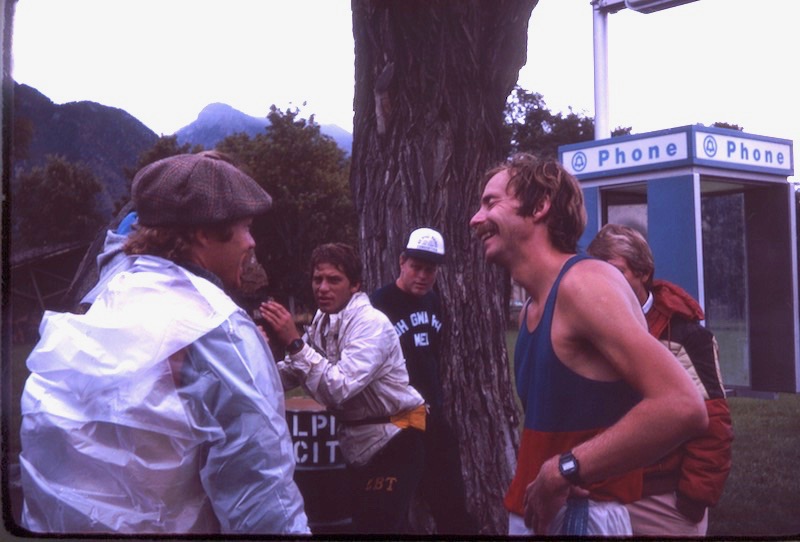

However, as the finish line neared, there was no roaring crowd, hyped-up finish line announcer or glaring football stadium lights. Instead, Ben’s wife and crew boss Mary told him: “The finish line is that phone booth”. Ben’s finish was applauded by race director Steve Baugh and a small handful of people who’d shown up after hearing occasional updates on Salt Lake City’s KSL radio station.

Steve Baugh awarded Ben the ceremonial winner’s pewter mug, an award Ben was not totally comfortable receiving. Over the past 30 hours, 5 minutes, Ben had reached the conclusion that the 1982 Wasatch was not a race at all. It was, instead, a 30-hour “suffer fest” that his California/Western States/sub 24-hour peers would never comprehend. Although, thanks to a myriad of sometimes comical events, his self-imposed standard of finishing in less than one day proved unattainable, Ben found consolation in the realization that he “stuck it out.”

Winner Ben Dewell is greeted by Race Director Steve Baugh (left)

at the phone booth finish line in Alpine.

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Ben Dewell describes the low-key phone booth finish line at Alpine City Park.

Audio Player

While Ben was enjoying the accolades of a hard-earned finish, Floridians James Gillis and Bill Athey were the only two runners still on the course. Leaving Lambs Canyon (mile 52) at 11:25 p.m. Saturday, after almost 18 hours on the course, they’d need to maintain that pace through the snowy night and rainy next day to reach the finish line before the 36-hour time limit expired at 5 p.m. Sunday.

They covered the 22 miles and two major, snow-covered climbs between Lambs Canyon and Brighton in 8 hours, 15 minutes. Daylight but a low cloud cover greeted them at the 8500’ elevation Brighton store (mile 75), where they arrived at 8:10 Sunday morning, 27 hours into the race. Rain mixed with accumulating snow hampered their climb to Catherine Pass (10,480’) and made the descent to Tibble Fork (mile 89) even more torturous. Snow greeted the two warm-weather Floridians again on the climb towards Box Elder peak in the Lone Peak wilderness area. At last, they reached the saddle and the “it’s all downhill from here” final 8 miles to the finish at Alpine.

Meanwhile, race committee newcomer John Grobben had long since completed his Affleck Park (mile 35) aid station duties and returned to his Springville home late Saturday night. Sunday morning found him bleary-eyed, trying to stay awake in church. The thought that there were, in all probability, runners still “out there” on the Wasatch course prevented him from really hearing anything that was said from the pulpit.

Sunday afternoon, he and a friend drove up to Alpine to see if anyone was going to make it to the finish line. It was rainy and cold. A low cloud cover hung over the valley, veiling all but the lower 1,000 feet of the treacherous Wasatch range.

John joined the small throng of spectators, curious, race DNFers and crew members near the phone booth at the Alpine City park as 5 p.m. and the 36-hour time limit approached. Word spread that only 2 of the remaining 19 participants were still on the course: Two lowlanders from Florida who’d never been on the course or previously run a single trail mile in Utah.

Race committee member (and current race director)

John Grobben caught the “Wasatch bug” in 1982.

(1985 photo courtesy of Dana Miller)

Excitement mounted as 4:30 p.m. brought the two survivors into view. James Gillis was clad in a t-shirt emblazoned with the Biblical verse from Isaiah 40:31: “But they that wait upon the Lord will renew their strength; they will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not become weary, they will walk and not faint.”

Weary they were. Faint they did not. John Grobben recalls “bawling like a baby” and one would have been hard-pressed to find a single dry eye among those who greeted James and Bill as they crossed the finish line in 35 hours, 25 minutes, 23 seconds.

John Grobben, who became race director in 1988, describes the moment he got “hooked on Wasatch”, a relationship that now stretches beyond 30 years.

Audio Player

Ben, James and Bill were the third, fourth and fifth runners to finish Wasatch in its first three years. They didn’t exactly soar like eagles but did survive the 1982’s “suffer fest”, proving the incredible tough course do-able.

1982 Runner Splits Tables (courtesy of Rick May – click link for pdf)

Article About 1982 Wasatch 100 in Ultrarunning Magazine

by Pete Gagarin

© 1980