by Laurie Staton

I did it on a dare.

Part of it was the Staton adventure gene I inherited from my parents. I began backpacking with a borrowed Trapper Nelson backpack when I was 13, began running with a borrowed sweatshirt when I was 14, and went off on the 28-day Northwest Outward Bound School when I was 17.

After all, why not? The inaugural Wahsatch Steeplechase marathon was not until late fall. I was registered for the Bonne Bell 10K that day, but happily forfeited my $6 entry fee to instead run the under-the-radar Flight of the Eagle 40-miler on a hot Saturday, September 6, 1980. One plausible reason was that I really didn’t need another lousy 10K time. But the real reason was this: adventure.

I don’t remember much of the Flight of the Eagle, other than it was a great day spent entirely running in the mountains with a few other like-minded adventurers. Somehow four of us Flight of the Eagle runners made it from Weber Canyon to a finish line near the Bountiful “B,” in 8:06, and what surprised me was how much fun we had simply running all day long. That was when Richard Barnum-Reece divulged his plan to run a hundred-mile race he would call the Wasatch Front 100 Mile Endurance Run.

For years, I would run up City Creek Canyon from the Deseret Gym. I met Greg Rollins in the hallways of the Gym, on his way to or from another run. I must have been fairly convincing in getting him out for the Flight of the Eagle, because he decided to join our rag-tag group for Wasatch as well.

Back then, I wore men’s old-school Adidas tricot running shorts, cotton t-shirts, and pair after pair of men’s Tiger X-Caliber GT running shoes. Women’s running shorts, jogbras, and shoes had yet to be de rigueur. As a handful of nascent trail runners, we were even a couple of years ahead of Bota-belts, so we crammed what snacks we could into JanSport fanny packs and carried quart Nalgenes filled with sugared tea, our magic drink for long runs.

Five of us started Wasatch on that cool, crisp morning on September 27, 1980: Richard Barnum-Reece, Steve Baugh, Jan Cheney, Greg Rollins, and me. The route started by going north on Highway 89, near the old Winder Dairy site, followed the Flight of the Eagle course up to what is now Chinscraper Hill, and then turned south on the ridge.

The Wasatch course was a little bit of a mystery from the ridgetop route on dirt roads and intermittent game trails through Hardscrabble Canyon to City Creek Pass and down to Affleck Park. From Lambs to the top of Catherine’s Pass, trails were well-maintained. From Catherine’s Pass down into upper American Fork Canyon was rough and rocky, and almost all but trailless. From there to the finish would be dirt roads and pavement.

Before Wasatch, we started with a hastily-thrown together but fairly democratic plan to each take a section of the 100-mile-or-so course, bring maps, and take turns leading the way through each section. It didn’t dawn on us that we would invariably be separated before we got much further than the first climb up to the ridge.

Steve Baugh and I somehow managed to stick together through Hardscrabble Canyon, the bushwhacking, and September heat. Once, up to our necks in scrub oak, we had yet again lost any semblance of a faint game trail and couldn’t imagine any way forward. Steve Baugh had taken it upon himself to be far more prepared than the rest of us – he actually had brought a large-scale forest service map, which at that point I thought was about as useful as a Texaco gas station Utah highway map, but it was a map nonetheless. I was rather cross with Steve on the topic of maps. I was thinking that quadrangles might have been more useful, but it’s like asking someone to bring a salad to the potluck and then turning up your nose when they bring Jell-O as the main ingredient: to some people, Jell-O means salad, not snack, not dessert. Lord knows what kinds of maps I had brought along. Then, at some point, even Steve and I got separated.

From Hardscrabble, the course continued on to an upper confluence of three canyons: City Creek, East, and Hardscrabble, and to what Wahsatch Steeplechase race director, McKay Edwards, later called The Brink. From The Brink, the course traversed the ridge down into Affleck Park. From Affleck Park, the course followed the paved road down to the frontage road bordering Mountain Dell golf course, then turned up Lambs Canyon. I continued into the dimming evening light to the rhythmic humming of crickets.

By nightfall, my one-person pacer/crew/ride home (also my ex) gave me an update: word had it that Richard Barnum-Reece and Jan Cheney had taken seven hours to reach Francis Peak. At that point, Jan Cheney bailed after about 15 miles and had gotten a ride from Steve Baugh’s wife, Evelyn, to be with his own wife, who was in the hospital about to have another child. Steve Baugh was rumored to have downed too many salt tablets, and made it to Lambs Canyon before his wife loaded him into the car and drove him home as well. Richard Barnum-Reece hadn’t been seen since Francis Peak and Greg Rollins was similarly unaccounted for.

My pacer was all set to carry along down jackets, a Svea stove and a cooking pot, some water, extra flashlight batteries, and even more provisions in a Lowe Alpine expedition pack. My pacer’s vehicle consisted of a 1949 Ford pickup with a mattress thrown in the bed of the truck.

Somehow Greg Rollins joined me and my pacer around Millcreek Canyon. We left lower Big Water via the Desolation Trail in light of a silvery moon with Greg Rollins (he was a couple of inches shorter than I) in front, me in the middle, and my pacer bringing up the rear. With darkness and the realization that I was little more than halfway through the course, a deep fatigue set in and I slowed considerably. I was overcome by sleepiness just from moving forward and looking at nothing other than a few steps in front of me for what seemed like a very long time. As Oregonian Morris “Red” Fisher would say many years later, I was passing rocks and trees like they were standing still.

We were trudging steadily along – somewhere in the deep, dark, quiet Millcreek forest – when we heard some snorting and thrashing about at fairly close range, and our dim flashlight beams finally landed upon a small bear. Just like Larry, Moe, and Curly, Greg Rollins stopped short, then I stopped, then my pacer stopped, and I was suddenly jolted out of my slow, meandering, semiconscious walk into being wide awake. We all held our breath. The bear paused for a moment, then moved noisily on and we resumed our march toward Brighton.

Dawn on the second day rejuvenated me and the cobwebs in my brain receded. It was 8:00 o’clock on a clear, crisp Sunday morning when I found myself at the Brighton Circle and headed directly for a tiny cabin called the Brighton Village Store. The store was vacant when I stepped inside, until one helpful soul emerged from the kitchen – Dave McCormick – a ski patroller in winter and a short-order cook in summer. My pacer and I sat down at one of the picnic tables covered with plastic red-checked table cloths. He greeted us with, “Good morning! What brings you to Brighton today?”

“We’re in a race,” I replied. Elaboration seemed like a frivolous expenditure of energy.

“Oh, really?” said Dave. “Who’s ahead?”

I took a long look out the store window from my table, then looked out the window on the other side of the store. I squinted and thought for a moment. What had happened to Greg Rollins? Where was he, anyway? After a few moments, I replied, “I guess I am.”

The pancakes were great, but it was time to continue up to Catherine Pass, down to American Fork Canyon, and on to the Alpine Loop. After a long cold night, I was back in shorts and a t-shirt again. The autumn-golden leaves rustled in a warm, gentle breeze.

Somehow I got wind that Greg Rollins was still in the race, so I decided I should stop to wait for him. After all, I thought, this trail we were travelling was an adventure, first; and a race, second. At about the top of the Alpine Loop he finally caught up with me, and from there we ran in together.

To this day I do not know what possessed me to do this, because in subsequent Wasatch 100s, I proved without a doubt to be cruel (I paused only momentarily to check on my good friend, Fred Riemer, as he lay in a ditch off the dusty dirt road near Pole Line Pass in 1983, waiting for his crew to bring him fluids) and heartless (the same year, I was running down Snake Creek Canyon with my friend Jay Aldous; when Jay stopped at his crew vehicle in the final miles, I told him I was going ahead without him to try to break 32 hours, which I missed by two minutes; and when he did cross the finish line that year, he didn’t stop, but proceeded to take off his running shoes, pour gasoline over them, and light them on fire, saying he would never run again). Was I cruel and heartless? Or just decidedly incapable of rational thought?

By Tibble Reservoir a truck pulled up beside me as I ran, and the driver rolled down his window to ask, “Are you in the 100-miler?”

“Yep.” My, how news had travelled.

Then, thankfully, Richard Barnum-Reece pulled up in his Volkswagen van – he had gotten lost in upper Hardscrabble Canyon, but had managed to build a fire, make a bivouac sack out of his t-shirt, and spend the night on the mountain. He had made his way to Affleck Park before he, too, called it quits.

“Richard! Where’s the finish?!”

“Follow me,” he said as he drove off as fast as one can in a Volkswagen van, curtains flapping, engine knocking, and quite possibly without a clue in the world exactly where that finish line would be.

Finally, finally, finally, Richard swerved into the deserted gravel parking lot at Sundance with my pacer’s ’49 Ford in a close chase. Just like that, it was over. It was a relief, in ways, but it also meant that the adventure was, for now, over too. It had taken us 35:01. I was dusty, dirty, thirsty, sweaty, scratched, scraped, sunburned, and sore. I desperately wanted to sit down, take off my shoes, change my shirt, and brush my teeth. I nodded off all the way home. The idea of food didn’t sound that great, but swallowing something cold, like a milkshake, sounded like a good idea. It must have been a slow night in the newsroom because there was something on the 10:00 o’clock news about a hundred miler and two finishers. I could barely keep my eyes open.

In addition to an accumulated fatigue, my body had a hard time regulating temperature – I started shivering when it was really a very mild 75 degrees. An hour later I was wide awake, then I’d hit a wall and couldn’t do anything but sleep. I was physically and emotionally spent not only from staying focused for two straight days, but from preparing myself for an adventure I never knew I could actually be ready for.

On Monday morning, my chemistry teacher announced there had been something about a hundred-miler in the newspaper box scores next to girls’ high school tennis matches, and how I had run in it. I winced because I knew that my familiar but feeble explanations were about to follow. But before I said a word, the girl in the seat in front of me turned around and in all honesty asked, “Why would you do something like that?”

After that, acquaintances would joke with me, “You really don’t have to run all that way. We can just drive you there,” but I never really came up with a very good answer to that question until a few decades later. And even then, I didn’t come up with anything original. I just say what my good friend Rick Gates said. “Because I can.”

In the Deseret Gym hallways, Greg Rollins looked at me askance whenever he saw me, and not too much later, I’m sure of it, tried to duck when he saw me or ignored me altogether, possibly in an effort to avoid getting involved in yet another harebrained idea. I don’t know that he ever ran another ultra or ran again period.

A couple of months later, in November of 1980, I ran Richard-Barnum Reece’s bitterly cold Goshen to Jordan road 50-miler. In 1981, I dabbled in triathlons and ran my first sub-three-hour road marathon. On my birthday in 1982, Jay Aldous and I circled the East High School track for 24 hours (101 miles and 97 miles, respectively – I crashed on the infield while Jay kept running), accompanied by visiting friends and lap-counters, cardboard pizza, danceable music, general silliness, and probably some beer. I started sending a monthly ultra-newsletter from my Smith Corona to an unsuspecting group I named the Wasatch Alpine Striders (possibly distantly related to the curious malapropism, wasalpstriders?). I didn’t run Wasatch again until 1983, when there was a massive field of 41. But that is another story.

In the past 37 years, I’ve been fortunate to have experienced achievements and disappointments; spectacular falls, injuries, and recovery from surgery; course records and personal bests; DNS’s, and DNF’s; ultras from 50K to multi-day, on the trail, road, and track; and a multitude of things large and small that are the stuff of life intervening. I have no idea exactly how many ultras I’ve run.

But I have come full circle – I look forward to running simply as an adventure. For me, adventure is not just getting to the finish line, but also about everything in between. Adventure is much different from “conquering thyself” or anyone else, for that matter. Adventure draws on passion and imagination as much as it does on resolve and grit.

I’ve been a runner for more than a lifetime. I love running and I can’t imagine that will ever change. If I’ve ever been a distant cousin to fast, I’m now an even more distant shirt-tail relative to fast, but that doesn’t matter. I still keep running because I love it and I can and because … there are these lists. These ultra career longevity lists, maintained by ultra historian, Nick Marshall, I was blissfully unaware of until a few short years ago. But that, too, is another story.

# # #

This narrative would not have been complete without collaboration with and information from Dana Miller.

©2017 LJ Staton

Dana Miller adds:

Pictured below are 4 of the 5 participants in the inaugural, 1980 Wasatch Front 100 Mile Endurance Run. I have not been able to find a photograph of Greg Rollins.

Laurie Staton and Greg Rollins were the first Wasatch 100 finishers. They finished the 1980 Wasatch 100 in a tie in 35 hours and 1 minute.

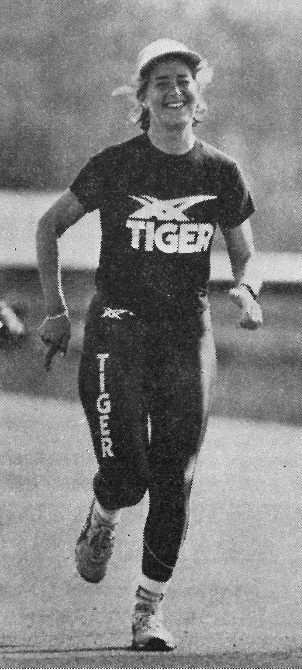

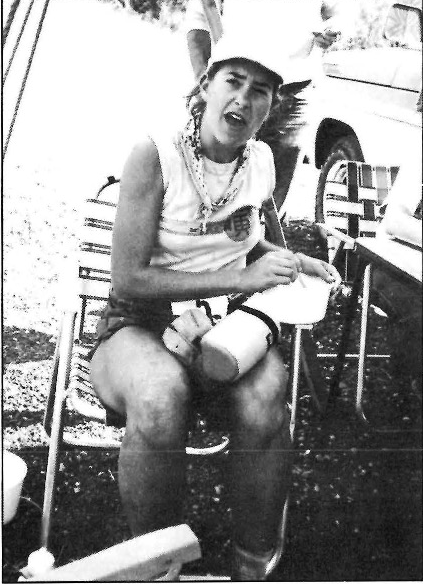

Laurie on her way to women’s course record victory at the Oregon TAC 50 Mile Ultra Championship. Grants Pass, Oregon (March 30, 1985).

(Photo used by permission from Ultrarunning magazine)

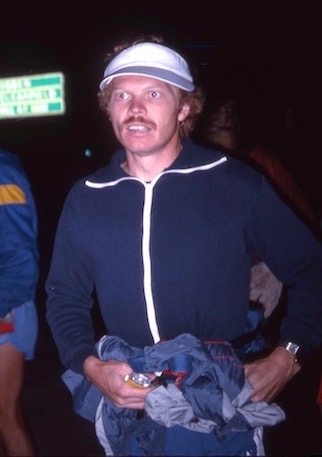

Steve Baugh dropped out at Lambs Canyon (50 miles).

Steve Baugh at the start of the 1983 Wasatch 100, which he DNF’d.

(Photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

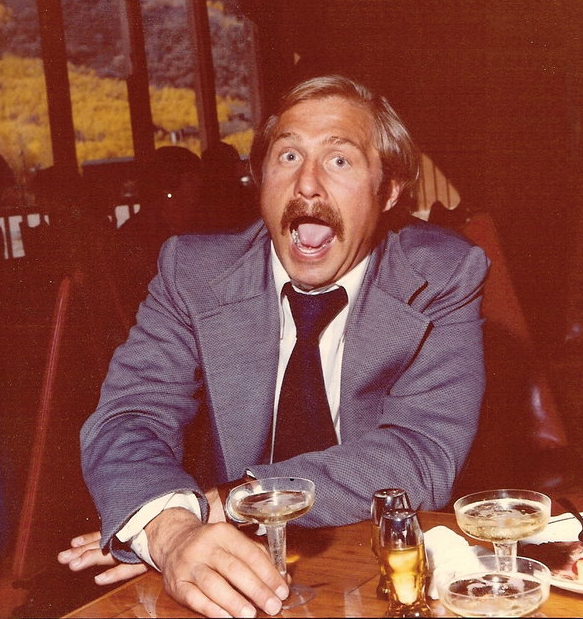

Wasatch 100 founder Richard Barnum-Reece dropped out at Affleck Park (mile 35) after

spending a cold night in Hardscrabble Canyon.

The Richard Barnum-Reece we knew and loved. Richard passed away in 2008.

(Photo submitted to Find A Grave website)

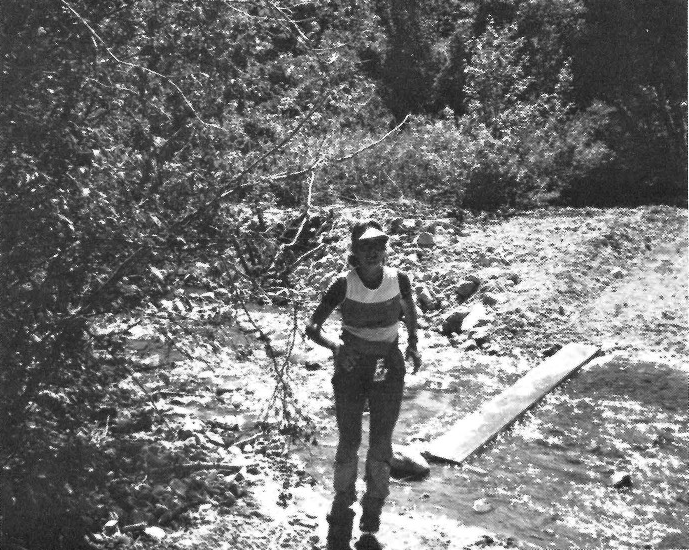

Bair Gutsman founder Jan Cheney dropped out near Francis Peak (15 miles) so that

he could return home to be with his wife, who was in labor.

Jan Cheney during a 2014 Mr. Goodyear’s Neighborhood interview.

(Photo courtesy of the Banyan Collective)

Laurie Staton and Greg Rollins finished the first Wasatch 100 together in 35 hours and 1 minute after she waited for Greg so they could finish together. In addition, Laurie went on to Wasatch 100 women’s victories in 1983, 1984 and 1987, setting new women’s course records in 1983 and 1987. In 1986, Laurie was one of the first two women to break the 30-hour barrier at Wasatch. She earned her 10th Wasatch finisher’s ring in 2011, a remarkable 31 years after her first finish!

In addition to her successes on the Wasatch trails, Laurie ran the 6th fastest women’s road 50-mile time in 1983 (6:53) in the U.S. and her course record 112 miles, 1124 yards in 24 hours at Megan’s Run in 1988 was 2nd best for U.S. women in 1988.

Laurie completed the Buffalo Run (UT) 50km in 2017. Her amazingly diverse and successful ultramarathon career now spans 36 years, 194 days and she’s not done yet. Here are a few of Laurie’s favorite trail ultra photos. Enjoy!

Laurie Staton crosses the creek entering the Affleck Park (mile 35) aid station on the way to another women’s victory in 1984.

(Photo used by permission from Ultrarunning magazine)

Laurie takes a strategic 49-minute aid station break at Big Mountain on her way to a 4th victory and new women’s course record (28:39) in the 1987 Wasatch.

(Photo used by permission from Ultrarunning magazine)

24 years later, Laurie cruises into the Big Mountain (mile 38) aid station in the 2011 Wasatch 100, en-route to her 10th finish.

(Photo courtesy of Laurie Staton)

Laurie celebrates her 10th Wasatch 100 finish in 2011 with another of the original, 1980 Wasatch 100 starters, Steve Baugh. Steve Baugh was the race director from 1981 – 1987 and is still on the race committee.

(Photo courtesy of Laurie Staton)

Laurie (center) at the start of the 2017 Buffalo Run 50km with long-time friends Ed Masters (L) and Fred Reimer (R). Fred is a 16-time Wasatch finisher and Ed has completed the race 3 times.

(Photo courtesy of Laurie Staton)

© 1980