by Dana Miller

Richard Barnum-Reece conceived the first Wasatch Front 100 Mile Endurance Run sometime during the summer of 1980. Richard was a rugby player-looking runner but was also a true entrepreneur and more than a little whacky. Those characteristics and his willingness to tackle the role of race director had, by 1979, already yielded two of Utah’s earliest trail races: the 40-ish mile Flight of the Eagle and the Park City 40-Miler.

The Western States 100 (1977) and Old Dominion 100 (1979) had been well received by the small and tight-knit trail ultrarunning community. By 1979, it’s third year, Western States drew 163 runners. That same year, its first, Old Dominion attracted 45 participants. Western States used the Sierra Nevada Mountains as its playground and Old Dominion was staged in the Appalachians. What about a 100-miler in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains? I seriously doubt that Richard Barnum-Reece’s motivation was “us too” jealousy. He’d already proven his love for the Wasatch Mountains and, I believe, wanted to let runners get to know them the way that he did. The hundred-mile distance intrigued him but also appealed to his natural attraction for the novel and the extreme. “So, you can run a marathon? Tackle this baby…it’ll kick the shit out of you!” seems like something Richard would say.

During the summer of 1980, Richard Barnum-Reece told Steve Baugh about his idea of staging a hundred mile trail race in the Wasatch Mountains and asked Steve if he was interested. Of course he was! Steve had done both of Richard’s trail races plus they’d spent a few trail miles together over the past couple of years. Richard had a pretty good idea where he wanted the race to start (on Highway 89 near Winder Dairy, just north of where I-84 enters Weber Canyon southeast of Ogden) and finish (Sundance Ski Resort) but asked Steve to map a route between these two points. Richard figured the distance would be roughly 100 miles.

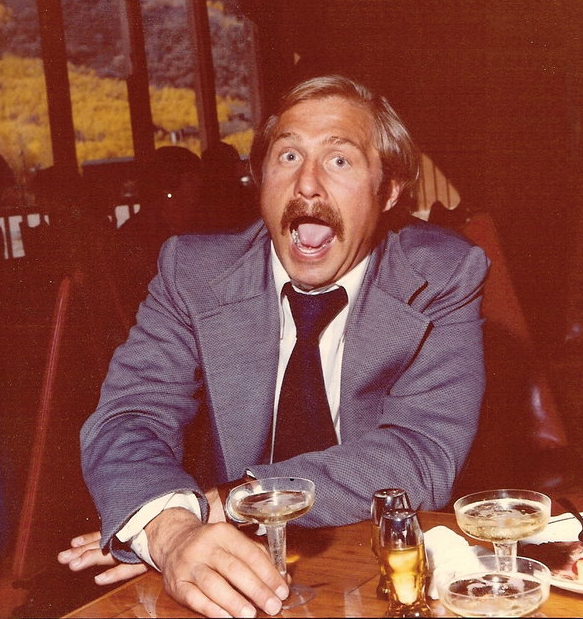

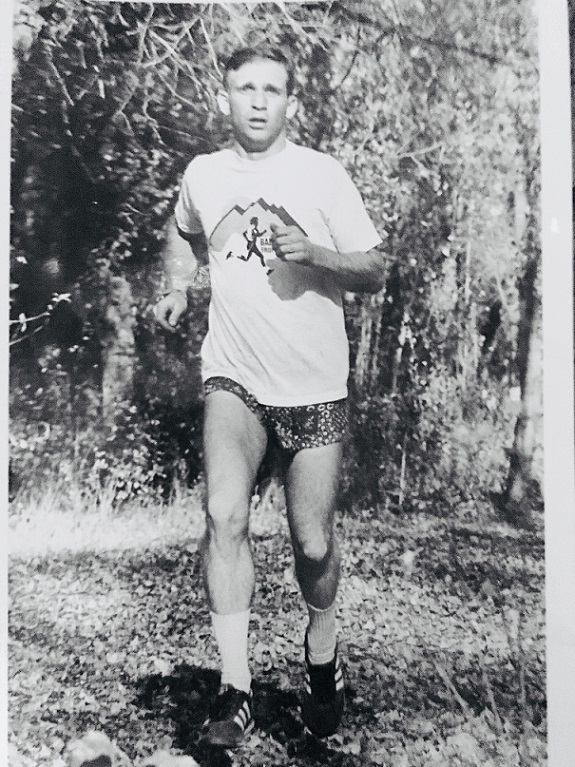

Richard Barnum-Reece in his natural habitat.

(photo submitted by a friend to Find A Grave website)

At this point, I’d like to emphasize that Richard Barnum-Reece and Steve Baugh were as different as night and day. As highlighted in the history article “Before There Was Wasatch,” Richard was loud, flamboyant, unconventional and took pleasure in being controversial. Steve Baugh, on the other hand, was a 30-year old Boy Scout by comparison. Steve was self-effacing, shy and pretty well the epitome of a conservative Utahn. He was, however, as tough as nails, fiercely self-reliant and loved being in the mountains. That the inaugural Wasatch 100 blended Richard’s outlandishness with Steve’s quiet independence should be no surprise.

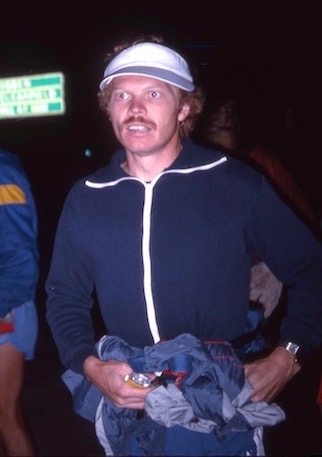

Steve Baugh – 1980 Wasatch map master.

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

The first Wasatch Front 100 Endurance Run was set for September 27-28, 1980. From what I’ve been able to learn, there wasn’t a lot of publicity about the race. Instead, news of the event circulated within the small Utah trail ultrarunning community and may even have been limited to the handful of runners who did Richard Barnum-Reece’s Park City 40-Miler and Flight of the Eagle races that same summer. The Flight of the Eagle (40 miles) was held on September 6th, just three weeks prior to the first Wasatch. Three of the four Flight of the Eagle participants (Greg Rollins, Laurie Staton and Steve Baugh) would also toe the Wasatch starting line.

There wasn’t a lot of organization to the 1980 Wasatch 100. As mentioned, Steve Baugh agreed to attempt mapping a route. Using Forest Service 1:24000 scale quadrangle maps, Steve highlighted a point-to-point course consisting of cross-country route finding, existing trails, dirt and paved roads. The route frequently traversed private lands but no attempt was made to gain permission from the landowners.

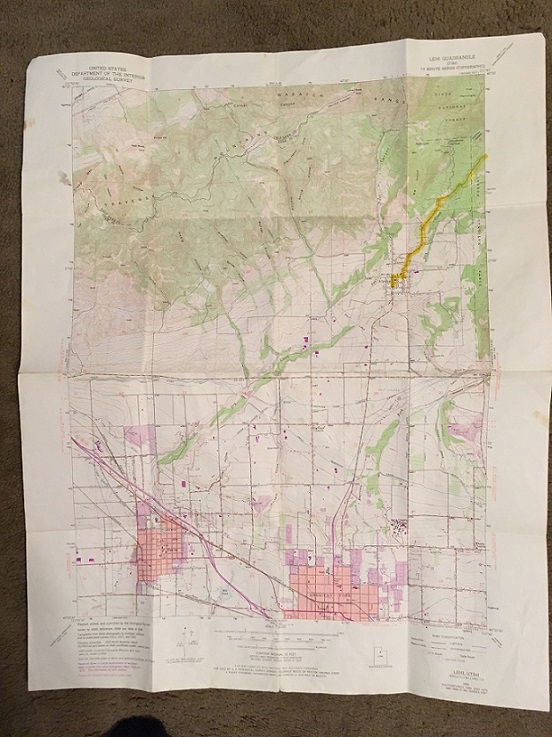

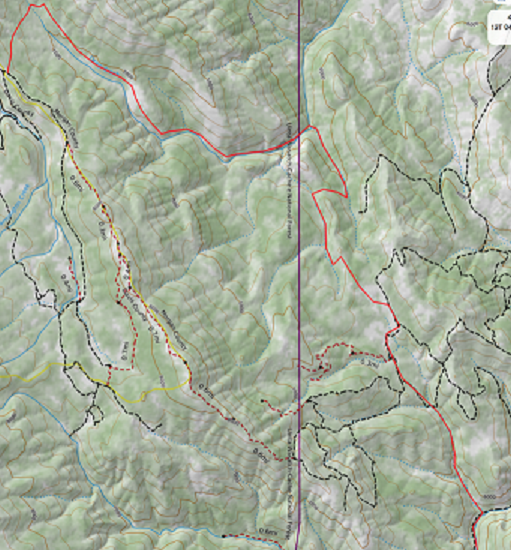

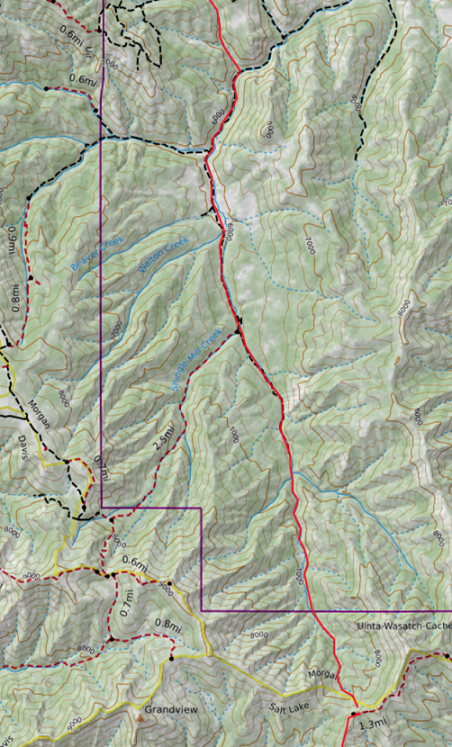

A sample of Steve Baugh’s marked quadrangle maps,

this one highlighting the 1981 finish.

(photo courtesy of Steve Baugh)

Steve highlighted a suggested route on his Forest Service maps. The maps were detailed enough to provide a skilled map reader with sufficient information to keep him/her from getting lost. However, just because the route was marked didn’t mean that: 1) a trail existed; 2) the trail was marked; or 3) that any of the original five runners had ever covered the designated route. This, of course, resulted in several challenges as the actual event unfolded. Steve Baugh also estimated the distance at 100 miles or so (the course wouldn’t be measured until the following summer).

The original Wasatch 100 route went:

- From the start at Winder Dairy on Hwy 89 east of Hill Air Force Base up to Chinscraper

- The ridgeline SSE to the dirt road north of Francis Peak

- The dirt road past Francis Peak and down to the Maintenance Sheds

- ENE from the Maintenance Sheds, then SE to the Narrows

- S up Hardscrabble Creek to City Creek Pass

- SE down to Affleck Park

- S down the paved road (Hwy 65) to Mountain Dell

- E along the side of I-80 to Lambs Canyon

- S into Lambs Canyon, then over Bear Ass Pass to Millcreek Canyon

- Up Millcreek Canyon to the end of the paved road at Upper Big Water

- Up the trail to Dog Lake, Desolation Lake, Scotts Pass, then down Guardsman Pass Road to the Brighton Store

- Up to Catherine Pass, then SE and down Dry Fork past Tibble Fork to American Fork Canyon

- Then SE on the Alpine Loop to the finish near Sundance

By the time “race” day rolled around, five experienced, local trail runners planned to tackle the first Wasatch 100’s great unknown. No one I’ve talked to remembers actually registering for the race or paying an entry fee. According to Steve Baugh, however, Richard Barnum-Reece did have a few race t-shirts screen-printed. What a treasure it’d be to locate one of those 1980 shirts! The five original Wasatch 100 entrants included: Richard Barnum-Reece (organizer); Steve Baugh (map guru); Laurie Staton; Greg Rollins; and Jan Cheney (Bair Gutsman and Beehive Track Club founder).

Jan Cheney recalls that he didn’t learn about Laurie Staton’s plan to attempt Wasatch until Thursday night before the race. He and Greg Rollins only half-jokingly expressed their concerns about “a woman” in the race. That thought, however, hadn’t even entered Laurie’s head despite the fact that only a handful of women had finished a 100-miler prior to 1980.

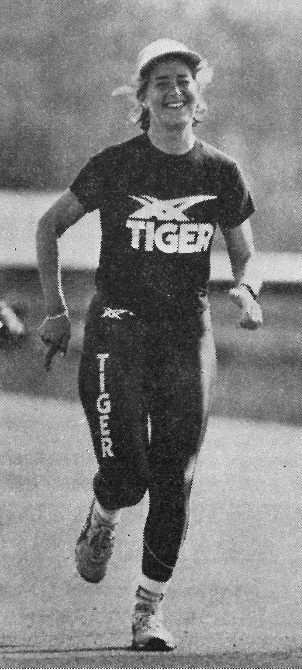

Laurie on her way to women’s course record victory at the Oregon TAC 50 Mile

Ultra Championship. Grants Pass, Oregon (March 30, 1985).

(photo used by permission from Ultrarunning magazine)

Excerpt from Laurie Staton 12-8-17 interview. Laurie Staton talks about her background and why being the first woman to run Wasatch didn’t even enter her mind.

Audio Player

On Friday night before the race, Laurie Staton hosted a carbo-loading spaghetti dinner for the entire field of 5. This gave the runners a chance to review Steve’s planned route and maps plus strategize about how to tackle 100 miles. The course was not marked and the five runners did not receive any narrative directions. Laurie Staton recalls that they agreed that one of them would be in charge of group navigation for each section of the route. So, it appears that they planned to stay together for the entire 100 miles. Evelyn Baugh, Steve’s wife, agreed to be the sole mobile aid station. Aid would be provided wherever Evelyn could drive the Baugh family’s aging vehicle in time to meet the runners along the route.

When I asked Steve Baugh about the group’s pre-race thoughts, he explained that there wasn’t any hype, it was more of an adventure…”to see if we could do it” than a race or event. “Just a small group of runners who loved the mountains getting together for the weekend to see if they could run 100 miles.”

Wasatch #1 got underway without a lot of fanfare on a beautiful fall Saturday morning, September 27th. The weekend’s weather forecast called for clear skies, calm winds and seasonally warm temperatures (high 70’s) in the afternoon. Within the first few miles of the steep climb toward what later became known as “Chinscraper”, the group’s plan to stay together and share navigation duties fell apart as Richard Barnum-Reece and Jan Cheney lagged behind. As inevitably happens in an ultra, they’d have to go to Plan B, which was made up as they went.

Jan Cheney, former Weber State University runner, Bair Gutsman

and Beehive Track Club founder.

(photo courtesy of Jan Cheney)

Excerpt from Jan Cheney 12-9-17 interview. Jan Cheney shares his memories of 7.5 hours with Richard Barnum-Reece from the start to Francis Peak, where he dropped out.

Audio Player

Laurie, Greg and Steve negotiated the faint hunting and deer trails past Chinscraper to the top of the ridge north of Thurston Peak, then made their way south along the ridgeline towards Francis Peak and eventually the Maintenance Sheds about 15 miles into the race.

Excerpt from Laurie Staton 12-8-17 interview. Laurie describes the 1980 Wasatch route, or lack thereof.

Audio Player

Steve Baugh’s now infamous Forest Service maps seemed to show a trail dropping off the ridge on the east side of the Maintenance Sheds. After getting refueled from Evelyn’s mobile aid station (hard candy, sandwiches, candy bars, fruit and lots of water), the lead trio headed east off the ridge, hoping to follow a trail to the Narrows at the north end of Hardscrabble Canyon. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a clear trail and the group ended up bushwhacking downhill for several hours before finally hitting the bottom of the drainage and Hardscrabble Creek at about Mile 22.

This is the route the runners were supposed to take from

the Maintenance Sheds to the mouth of Hardscrabble Canyon.

(map courtesy of Phil Lowry)

Excerpt from Steve Baugh 12-9-17 interview. Steve talks about bushwhacking after heading east from the Maintenance Sheds (mile 14) and eventually making their way up Hardscrabble Canyon.

Audio Player

Knowing Steve, I imagine he felt personally responsible for every scratch, scrape, bruise and hour lost in this section. (As it turned out, there was a faint trail that dropped northeast from the Sheds but they had missed it.)

Running the seven miles up Hardscrabble Creek proved to be both the most difficult and most memorable section of the original Wasatch 100 course. The runners followed Hardscrabble Creek, mostly just bushwhacking their way southward from one side of the creek to the other as they made their way towards City Creek Pass. Steve remembers crossing the creek 19 times but others claim it was closer to 30. Finally making it to the head of Hardscrabble, the climb up to City Creek Pass was so steep that jokes were the only thing the kept them going in the afternoon heat.

The infamous Hardscabble Creek section of the 1980 Wasatch 100 course.

At the south end (bottom) it intersects the current route at about mile 26,

City Creek Pass. (map courtesy of Phil Lowry)

In the meantime, back to Richard and Jan. They did make it to the ridgeline above Chinscraper despite Richard twisting his ankle badly along the way. Near Francis Peak, after 7.5 hours on the trail, Jan had an epiphany. Prior to the start, his very pregnant wife had only half-jokingly told him that he could do the race but if he wasn’t home for the birth, she’d be looking for a good divorce lawyer. Well, the light came on and Jan got his priorities straight and started looking for a way off the mountain. As luck would have it, Evelyn Baugh found the two long-overdue runners at about this time. After getting Richard re-stocked for the trail, she gave Jan a ride down off the mountain and home. Sometime after 2 p.m., Richard Barnum-Reece bid the Maintenance Sheds good-bye and, also failing to find “the trail”, began his own afternoon of bushwhacking down to the Narrows.

Steve, Laurie and Greg discovered that the trail from City Creek Pass (a point called “The Brink” on the Wahsatch Steeplechase marathon course at the time) down to Affleck Park was a freeway in comparison to their last dozen wild and crazy near trail-less miles. At Affleck Park, on the road to East Canyon and Big Mountain Pass, Evelyn again provided mobile aid and shared the news that Jan had gone home and Richard was now on his own.

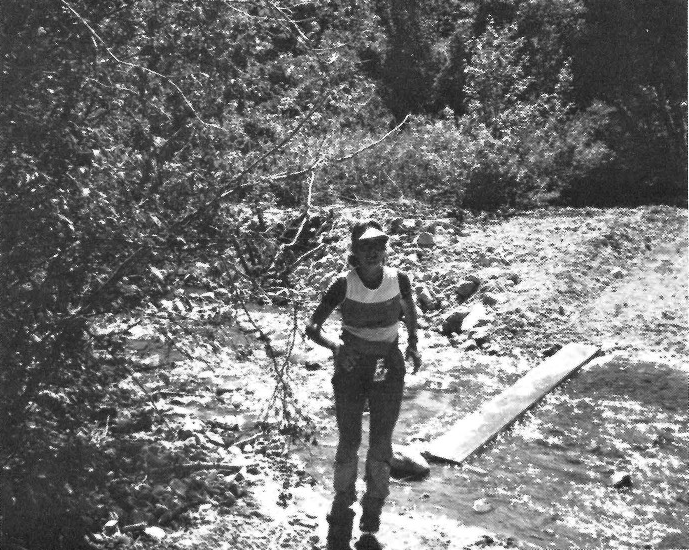

Laurie Staton crosses the creek entering the Affleck Park (mile 35) aid station

on the way to another women’s victory in 1984.

(photo used by permission from Ultrarunning magazine)

Steve, Laurie and Greg then ran down the paved road (Hwy 65) to the East Canyon exit off Interstate 80. From there, they ran along the side of the freeway guardrail east and uphill to Lambs Canyon, about the mid-point of the race. Steve decided to drop out at Lambs Canyon because he was having serious stomach issues plus it was now dark and he was worried about Richard Barnum-Reece. While Laurie and Greg continued up Lambs Canyon, Steve and Evelyn drove back to Affleck Park with hopes of finding Richard. Instead, at Affleck Park they found Richard’s brother, “Crazy Bob” sitting in a lawn chair by a fire, drinking beer. He planned to wait for Richard.

Excerpt from Steve Baugh 12-9-17 interview. Steve shares his recollections of dropping out of the race at Lambs Canyon, then trying to find Richard Barnum-Reece.

Audio Player

It was near midnight and although he was concerned about Richard, Steve decided there wasn’t anything they could do. He and Evelyn drove down the canyon into the Salt Lake Valley. On the way, Steve grew increasingly worried about Richard so decided to stop by the Salt Lake County Sheriff Office to alert Search and Rescue. They refused to initiate a search for Richard in the middle of the night and told Steve to call them back the next day if he didn’t show up.

After hours of bushwhacking down to the Narrows at the mouth of Hardscrabble, Richard turned south into Hardscrabble Canyon where he struggled through its two-dozen stream crossings and even more bushwhacking. He finally reached the head of Hardscrabble Creek and started the climb towards City Creek Pass just as it got dark. As his flashlight batteries gave out, he found himself on a cliff band on the east side of the drainage and realized that he couldn’t see well enough to continue safely.

Richard Barnum-Reece

(photo from his self-written obituary published in the Desert News, February 2-3, 2008)

He did have matches with him, so found a relatively flat area to build a fire. He spent the night by the fire with his knees pulled up towards his chin and his t-shirt and jacket pulled down over his legs for additional warmth. After a very cold night, dawn was a very welcome sight. Hungry, cold and tired from a sleepless night, he made his way to City Creek Pass and found the trail to Affleck Park. I can only imagine the tale Richard told Crazy Bob as they drove back down into Salt Lake Valley. Richard even penned a post-race article about a fictitiously-named runner getting lost in Hardscabble and blamed Steve Baugh’s mapping skills for the runner’s plight and cold night in the mountains.

At about the same time, Laurie Staton and her pacer arrived at Brighton (approximately mile 75) and went into the store to see if they were serving breakfast yet. In her story, she recounts Dave McCormick, who was tending the store that morning, asking her what she was doing in Brighton so early on Sunday morning. “We’re in a race,” she replied. “Oh really?” Who’s ahead?” Dave asked. After realizing that Greg Rollins was nowhere to be found, she replied, “I guess I am.” Apparently, somewhere after Upper Big Water in Millcreek Canyon, Greg Rollins had fallen behind.

Well-fed and ready to tackle the final quarter of the race, Laurie and her pacer made their way up to Catherine Pass, then dropped down into the Dry Fork drainage, continuing on towards Tibble Fork. Laurie recalls: “Somehow I got wind that Greg Rollins was still in the race, so I decided I should stop to wait for him. After all, I thought, this trail we were travelling was an adventure, first; and a race, second. At about the top of the Alpine Loop he finally caught up with me, and from there we ran in together.”

Neither Greg nor Laurie knew exactly where the finish line was. It’s likely that even Richard Barnum-Reece didn’t know. All we do know is that Richard survived his overnight stay in Hardscrabble, got to Affleck Park, then drove his aging Volkswagen van to find the two remaining runners. Catching up with them on the Alpine Loop, Laurie recalls that Richard shouted “Follow me!” and proceeded to lead the duo down the road driving “off as fast as one can in a Volkswagen van, curtains flapping, engine knocking and possibly without a clue in the world exactly where that finish line would be.”

Somewhere near Sundance, Richard finally pulled into a gravel parking area and, as Laurie and Greg arrived together, declared the very first Wasatch Front 100 Mile Endurance Run finished after 35 hours, 1 minute and 21 seconds.

And so the Wasatch 100 story began. The results leaked out and into the newspaper box scores, “next to girls’ high school tennis” according to Laurie Staton. In his 1980 Ultrarunning Summary, historian Nick Marshall wrote: “…the small print Wasatch Front results that appeared in two Utah newspapers list only her [Laurie Staton’s] time as 35:01:21, with his [Greg Rollins’] given as 35:01:22. What gives? Does it mean this is a case where a woman is trying to say she tied with a man rather than admit the dastardly truth that she thoroughly whipped him?” It appears that, true to his never-shy-from-controversy form, Richard Barnum-Reece was trying to say exactly that.

Laurie Staton, however, didn’t buy into Richard’s attempt to make an issue of which runner “deserved” recognition as the winner.

Laurie Staton at the 1992 Wasatch 100 finish line

at Theatre in the Pines near Sundance

(photo by Dana Miller)

Excerpt from Laurie Staton 12-8-17 interview, in which she talks about waiting for Greg Rollins and finishing together in a tie.

Audio Player

It’s doubtful that Laurie, Greg, Steve, Richard and Jan realized that their wild weekend adventure set the stage for an event that would become one of the most historic and prestigious hundred mile races in the world. Their efforts also helped establish Wasatch’s legacy of rugged beauty, unpredictability and self-reliance.

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Steve Baugh, Laurie Staton and Jan Cheney for sharing their 1980 Wasatch 100 memories. The many vivid details they provided give us a glimpse of what it was like to do that first Wasatch 100 and what went on inside their warped minds. Here are, from left to right, Steve, Laurie and Jan 37 years later.

© 1980