by Dana Miller

Sometime during the winter of 1980-1981, Richard Barnum-Reece accepted the Sports Editor position with a newspaper in Laramie, Wyoming (Note: Probably the Laramie Boomerang although Richard did not mention the job or newspaper’s name in his self-written obituary). Realizing that trying to grow and develop the Wasatch 100 from 400 miles away would be almost impossible, he asked Steve Baugh if he was interested and willing to take over both the Wasatch 100 and the Park City 40-mile races.

Steve Baugh at the 1982 Wasatch 100 pre-race meeting

(photo by Mary Dewell, courtesy of Ben Dewell)

Steve said “yes”, of course. Although he was significantly more interested in running the 100-miler than directing it, he recognized that if he wanted the race to go, he’d probably need to be the one to do it. He wasn’t as interested in the 40-mile event, so approached 1980 finisher Greg Rollins about taking that one. It died a quiet death…never to be staged again.

With Steve’s 1980 Wasatch 100 DNF at Lambs Canyon experience and failing to stay on the designated route from the “green sheds” (later called the Maintenance Sheds) to the mouth of Hardscrabble Canyon, he knew he’d have to get the course clearly defined. That was critical to standardizing the route and to attracting runners who might lack his intimate knowledge of the Wasatch range east of Salt Lake and Utah valleys.

So, Steve spent a lot of the summer of 1981 “wheeling” the proposed course. Wheeling the course consisted of pushing or dragging a revolution counter-equipped bicycle wheel for the entire course, one section at a time. By multiplying the number of revolutions by the wheel’s circumference, he’d get a pretty reliable measurement of distance. He removed and rigged his 10-speed bike’s front fork with a broom handle to make it easier to hang onto. That all sounds good on paper but imagine trying to push/drag the wheel over large rocks, over downed trees and along frequent cross-country routes you hope the runners will follow. Evelyn, Steve’s very patient and indulgent wife, would drop him off at one end of a trail section, then drive the couple’s ancient pick-up to the other end while trying to wrestle two young, normally wild and crazy boys. Evelyn should be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Evelyn Baugh was tireless in helping Steve establish the Wasatch 100

(1981 photo courtesy of Steve Baugh)

Imagine how strange Steve looked pushing that wheel! He recalls one amusing incident between Chinscraper and Thurston Peak (about 7 miles into the original course) when he came wheeling along a trail-less ridge and ran into a couple sheepherders. They were sitting near the ridgeline, eating lunch and keeping an eye on their sheep. “What in the hell are you doing?” was their immediate question. After explaining that he was measuring a 100-mile run course, he sat with them, eating his sandwich. He asked them about a pile of dead sheep he’d seen a mile or so north. “Must have been struck by lightning!” they speculated.

Interview with Steve Baugh about wheeling the course.

As Steve measured the course, he kept careful notes, recording distances and details to create narrative directions. Steve’s narrative directions are exactly that…almost conversational, interspersed with frequent compass readings and humorous anecdotes. For example: “At 5.4 miles there is a water hole called Cool Springs. There is a rubber hose sticking out of the mountain providing good cold water. Watch out for a black bull roaming this area. (He doesn’t have horns) Take a compass reading in front of the water hose. At about 200 degrees you can see a trail zig-zagging up to the ridge. That is the correct way.” Amazingly, he described the entire 100-mile route in just over 4 pages of single-spaced text! In typical deadpan form, Steve Baugh quipped: “Most of the runners got a kick out of them.”

Steve Baugh’s 1981 Course Directions (pdf)

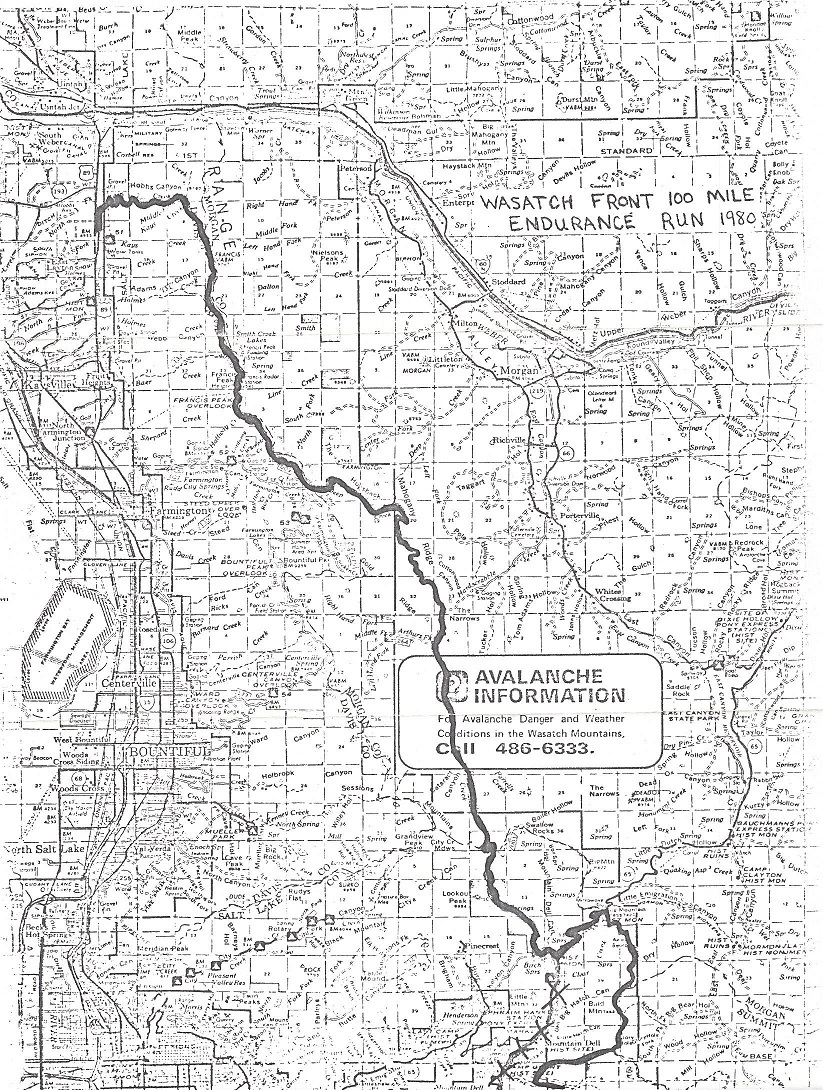

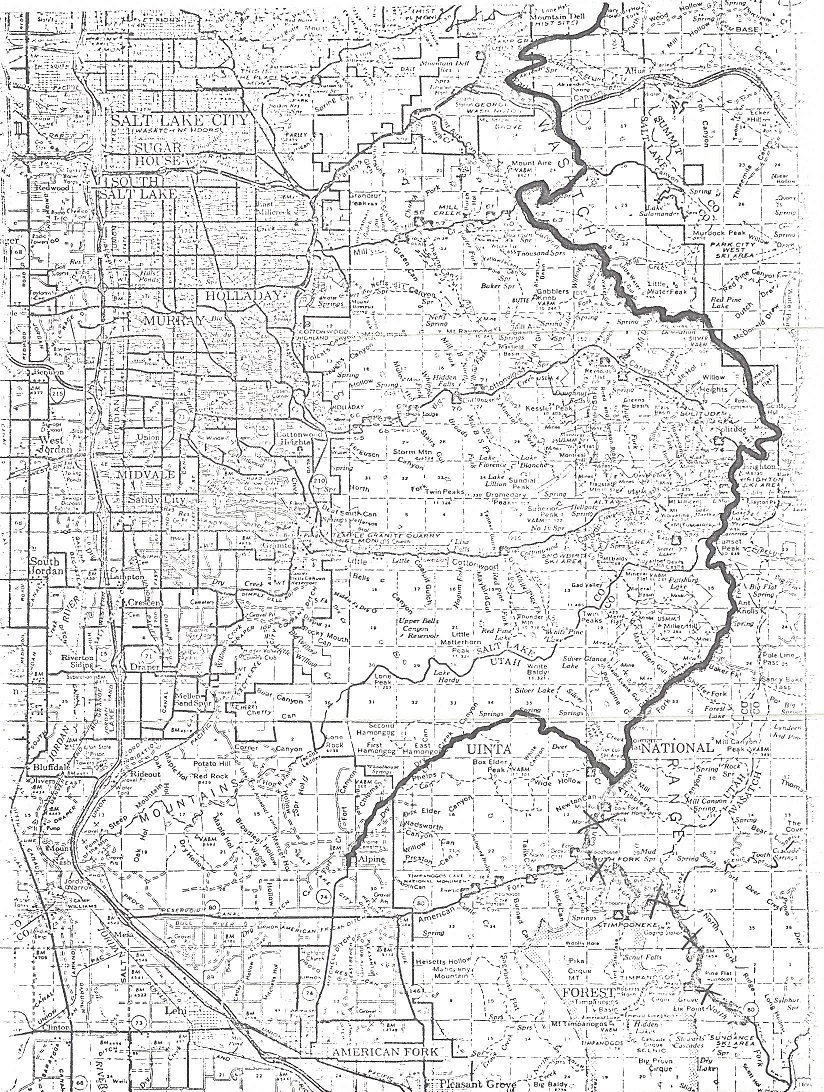

The 1981 course introduced two major changes to the previous year’s route. At Affleck Park in East Canyon (approximately mile 35) the course went up the paved road (Highway 65) to Big Mountain Pass then proceeded over Bald Mountain to Lambs Canyon. (In 1980, runners turned south at Affleck Park, running the paved road down to Lambs Canyon.) Also, the finish was moved from Sundance Ski Resort to the Alpine (UT) city park, which meant runners would turn northwest near Tibble Fork (approximately mile 89), then climb a trail into the Lone Peak Wilderness area before descending to Alpine.

Course overview map from the 1981 race packet

(courtesy of Rick May)

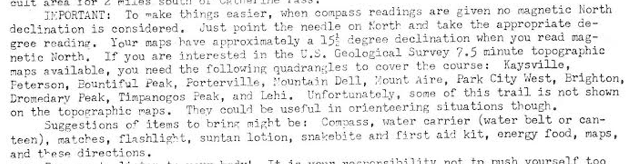

Part of Steve’s motivation for providing detailed narrative directions was practical. He was staging Wasatch with assistance of only one other member on the non-existent “race committee”: Evelyn, his wife. He knew he could not mark much of the course. Runners would have to take a compass and carefully follow the directions. The instructions runners received included this advice: “IMPORTANT: To make things easier, when the compass readings are given no magnetic North declination is considered. Just point the needle on North and take the appropriate degree reading.” Steve wasn’t kidding when he advised runners to bring a compass – they’d need it: “I remember seeing one of the runners in 1981 standing in the creek near Affleck Park, barefoot and reading a large quadrangle map with his compass in hand trying to make sense of where he needed to go next.”

In addition to measuring and describing the course, Steve made things really official by developing an actual entry form and runner information packet. The 1981 entry fee was $10. For that astronomical price runners got “a t-shirt, certificate, timing and a finish line.” For an additional $15, they could opt for what Steve called “a special award”. Steve recently recalled: “I think the special award was a hand engraved belt buckle if anyone made it under 30 hours. It was pretty lame looking. It was a plain piece of brass formed into a buckle engraved “Wasatch Front 100 Mile Endurance Run under 30 hours”. It probably would have been embarrassing to hand one out.” No mention was made of aid stations. Runners were expected to have a “handler”. If runners did not have a handler, they were required to acknowledge that they were responsible to have one.

Note the last paragraph: “Suggestions of items to bring might be: Compass, water carrier (water belt or canteen), matches, flashlight, suntan lotion, snakebite and first aid kit, energy food, maps and these directions.” Yes…a snakebite kit!

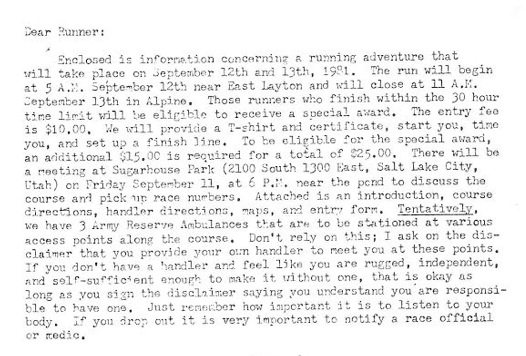

Based on his own experience running the previous year, he knew that runners could get in trouble. His pre-race letter stated: “Tentatively, we have 3 Army Reserve ambulances that are to be stationed at various access points along the course. Don’t rely on this…”

Although this level of support is sketchy by current Wasatch standards, it reflects more than just the fact that Wasatch was in its infancy. Steve Baugh loved being in the mountains, figuring things out and even didn’t mind getting lost once in a while. The 1981 Wasatch, although certainly more “race-like” than the “let’s see if we can do this” spirit of the previous year, still retained its orienteering/adventure feel.

In hopes of frightening off runners who weren’t ready for Wasatch’s difficulty and to help those who were ready be better prepared for Wasatch’s challenge, Steve provided the following race introduction:

First of all to give you an idea of what you are getting yourself into, here are some facts about the course. There is a total elevation change of 48,210 feet. 24,258 feet of uphill and 23,952 feet of downhill. From mile 1.2 to mile 6.2 the trail climbs up 4,691 feet. That is 938 feet per mile average. The highest elevation is 10, 480 feet near Catherine Pass. The lowest elevation is 4,880 feet near the starting line. This course requires that you not only be in excellent condition physically, but must always be alert mentally for changing trail condition and rattlesnakes. There are a couple of sections which require orienteering skills with a compass, as the trail fades and you need to pick it up again. One 3-mile section of trail in Hardscrabble Canyon crosses the creek 19 times. There are several streams along the way, however some of them are dry by September. The longest distance between handler access points is 20 miles. This area is from the green shed near Francis Peak to East Canyon.

1981 Runner Packet Instructions (pdf)

Despite Steve making the race sound so difficult (or perhaps because of it) seven runners toed the starting line at 5 a.m. near Winder Dairy on September 12, 1981. Similar to Western States and Old Dominion, the 1981 Wasatch had a 30-hour time limit. The seven runners included: Rick May (UT), Russell Belk (CO), Raymond King (CO), Gary Cross (CO), Steve Baugh and 2 runners from Oklahoma (possibly one with the last name “Drucker”). Steve was the only runner who had also started the inaugural 1980 race.

Interview with Steve Baugh about a runner from Oklahoma.

Interview with Rick May about entering the race.

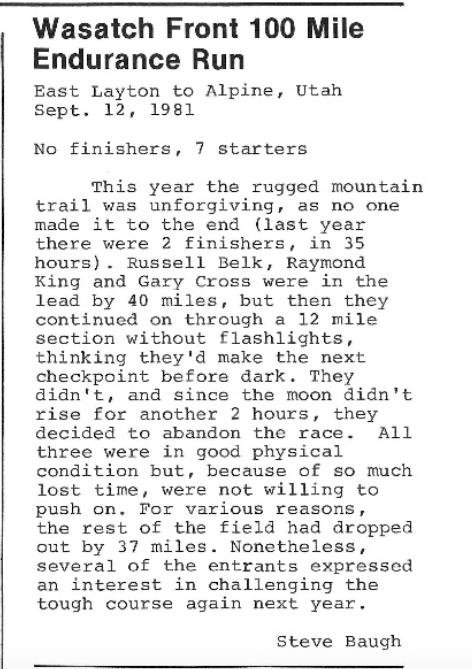

Steve’s recollections of the 1981 race are surprisingly brief. None of the 7 starters made it past Lambs Canyon. In fact, only 5 starters even made it past the “green shed” handler access point at Mile 17!

Rick May, who would go on to finish Wasatch 12 times, provided this additional information:

I also ran the 1981 race that had 7 starters and no finishers. I was ahead at Affleck Park (approximately 36 miles), but had to drop out with a sprained ankle. I learned the next day that the other runners did make it to Big Mountain, but did not take their flashlights on the section from Big Mountain to Lambs Canyon. As it was getting somewhat late when they started that section, it got dark and they got disorientated and lost. The story I heard was that they eventually stumbled out on the golf course by Lamb’s at around midnight and they all dropped out there.

Interview with Rick May about the lead runners.

Rick May – 1988 Pikes Peak Marathon

(photo courtesy of Rick May)

In the pre-race meeting at Sugarhouse Park, Steve advised the runners who did make it to Big Mountain Pass (mile 39) to take flashlights with them as they ventured towards Bald Mountain and eventually on to Lambs Canyon. For whatever reason, the lead group of 3 Colorado runners didn’t heed his advise…probably because they were confident of making it to Lambs Canyon (only 12-13 miles away) in the daylight.

Steve was anxious for the runners to have a good experience at Wasatch and to see at least a few make it to the finish line. As he waited near the Lambs Canyon I-80 exit, he became increasingly nervous about the 3 remaining Colorado runners’ progress and safety. The sun went down and darkness crept over the course. It usually gets dark around 8:00 p.m. on race day, so the runners had already been on the course for at least 15 hours.

Convinced that the runners were suffering the consequences of failing to take flashlights with them, Steve drove down the road from Lambs Canyon, pulled off the freeway and pointed his car in the direction where the now disoriented runners might be. He flashed the headlights on and off in hopes of providing the runners a beacon to follow. Apparently, the runners never saw the flashing headlights.

Interview with Steve Baugh about the lead runners.

Based on the runners’ reports, they spent several hours trying to figure out the route from Alexander Springs to Lambs Canyon…without flashlights and no moon! This was, admittedly, one of the most difficult sections of trail to follow even in the daylight. Keep in mind that it also was not marked! The narrative directions for leaving Alexander Springs state:

CAUTION: At 51.1 miles you must leave the main trail again. Another stream comes from the East and joins the creek you’ve been following. If you hear a louder river on your left, you’ve probably gone too far. Just before the Eastern flowing stream joins, there is a small wooden bridge to your left at about 100 degrees compass reading. We’ll try to keep this spot flagged but don’t count on it as someone may take it down. Cross the bridge and follow this new stream East on the North side. Follow this stream for nearly 11/2 miles until you come to a beaver dam waterfall. There is a big dead tree laying across the path. 30 to 50 yards up the stream from this point is another contributing stream coming from the South. Cross the stream you’ve been following just above the beaver dam in a shallow area and begin following the contributing stream that comes from the South on the West side. We’ll try to mark this area also. There are a couple of spots along this section of about 10 or 20 yards where the trail is covered with overgrowth of trees and bushes so you’ll need to bushwhack but not for long. Finally you come to a cement pipe where this stream is coming out of the mountain. Climb directly up above the pipe where the ground has been washing away heading Southeast until you come to a road.”

As detailed as these directions are, they didn’t do the runners any good. They could not read them without flashlights! In reflecting on this especially difficult-to-follow section of the course, Steve recently commented: “…this section of trail was hard to follow even in the daylight. I don’t know what I was thinking other than I was a novice race director and I liked adventure.”

Ultrarunning magazine published its first issue in May 1981. Steve’s summary of the 1981 race was included in the November 1981 issue:

Ultrarunning, November 1981, page 12

(used by permission from Ultrarunning magazine)

Steve did not get to award the coveted winner’s mug nor did he have the pleasure of handing out any of the $15.00 “special awards” mentioned in the race information letter.

Steve Baugh (2017) displays the 1981 Victor’s Mug

(photo by Dana Miller)

The 1981 Wasatch 100 Victor’s Mug is still unclaimed

(photo by Dana Miller)

In preparation for the 1981 race, Steve Baugh almost singlehandedly created the foundation for the Wasatch Front 100 Mile Endurance Run as we know it today. He also established Wasatch’s reputation as a tough race that favors self-reliant, experienced runners. In retrospect, Steve feels that the fact that no one finished in 1981 actually increased interest in the event!

© 1980